I started work at the Selmer factory in Holborn,

London, immediately after Easter 1964, as a Test Technician. John

Crocker

started the same day, also on Test. The chap in charge of Test was Ron

Fowler. Ron was born in Buenos Aires but had been brought up in Jamaica

and spoke with a West Indian accent. In looks he always reminded me of

a Mexican bandit, as depicted in films.

Amplifiers were coming off the production benches by the dozen so we

were kept very busy. Remember this was 1964 and every street in the

country could boast of at least one pop-group among its younger

residents, and they were all clamouring for amplification equipment.

(ED - at this time Selmer were making the hugely popular croc-skin

covered amps).

It has been my understanding that when the Davis brothers retired to

live in the south of France, they sold Musical & Plastics

Industries (MPI) to a Midlands firm which manufactured (among other

things) umbrellas! (ED - MPI was the parent company which owned Selmer

and also Selcol, a company which made plastic products). Apparently,

the umbrella business was on the rocks and they borrowed money from

bankers to buy MPI believing that the profits from MPI would pay back

the loan and also dig the umbrella business out of the mire. This did

not transpire, and the umbrella business dragged MPI down with it. The

bankers, fearful of losing their money, ditched the umbrella firm and

put a man of their own in to bring MPI back into the black. That man

was John Cochrane, an elderly and rather short of stature person, who

had worked successfully for them in the past. He came in as Chairman

and Managing Director and appointed Dick Twydell as Production

Director, in charge of the Theobalds Road, Holborn factory. And so it

was when John Crocker and I joined Selmers.

Selmer had been building organs for several years, but they used valve

circuitry which made them rather large, and they were mainly only

suitable for use in church halls and similar establishments. With the

advent of transistor technology organs could be made much smaller such

that they became suitable for home entertainment, and this opened up a

whole new market. Selmer began importing organs from Chicago Musical

Instruments (CMI), a large American company, but because of high import

duties they were rather expensive and this limited their sales. In the

early 1960's MPI concluded an agreement with CMI which gave Selmer the

franchise to build Lowrey organs from kits of parts which were shipped

over as 'Traypacks' and assembled into cabinets made by the Selmer

subcontract cabinetmaker, Rawson Sparfield. As the kits could not be

classified as complete instruments they did not attract a large import

duty, and this combined with excellent sales in the home entertainment

market, made the arrangement quite lucrative. At the beginning they

shipped over a model known as the TLO which was quite basic with no

frills, but gradually more sophisticated models were introduced which

incorporated Leslie speaker units, reverberation, automatic rhythm etc.

In the autumn of 1964 'OXFAM' organised a Pop Competition whereby

amateur groups throughout the country could enter regional heats, to be

judged for best performance, these being gradually whittled down and

the six best to be finally judged by a panel of celebrities at a gala

televised performance in the Prince of Wales theatre in Piccadilly.

Selmer were invited to provide the amplification equipment throughout

the event to which Twydell agreed, as it gave the Company an excellent

advertisement . The South London heats were held in Lewisham Town Hall,

and various members of our staff took turns to attend in order to keep

an eye on the equipment and to deal with any associated problems which

might arise. I was also in attendance at the Prince of Wales theatre,

and I recall that Cilla Black was one of the judges and that the

Manfred Mann group were engaged to play during a break in the

proceedings.

Initially, the test room personnel were also responsible for servicing

any returned equipment, but early in 1965 it was decided to separate

these functions, and two of the test staff were detached and relocated

in another area of the factory to carry out the service operation. This

left myself, John Crocker, Ron Fowler and two women inspectors. In

addition, it was arranged that the test facility would be carried out

in a small 'greenhouse' type structure erected in the production shop

rather than in an enclosed room away from the manufacturing area. I had

become quite friendly with Ron, and we often went out for a drink

together, and I was not surprised when he told me that he had accepted

a better job with a large firm nearer to where he lived. However, this

turned out to my advantage as shortly after he left, Mr Twydell asked

me to take over his job, and I was able to recruit Allan Baldwin to

join us.

At that time there were two people in R&D. John Hosey and Brian

Davis. John Hosey was responsible for the 'upside down' black and blue

range of amplification which came after the gold finish (ED :

croc-skin) range, also the PA100, which was based on a Mullard circuit, the Twin Lead 30, and the Stereomaster,

which the sales people wanted because the were selling stereo guitars. Brian

Davis developed the Taurus 60 (later called the Saturn 60) which was an all transistor

amplifier. Unfortunately it did not go well due to the frequent failure

of the germanium output transistors. In fairness to Brian it should be

stated that our competitors were not faring much better with their

transistor efforts, as these devices were quite new to us at that time,

and few people had much experience in using them.

.jpg)

February 1967 Selmer advertisement showing

the range of "upside-down" Blue-Black amplifiers referred to above.

Soon after Ron went, John Hosey also left, and then a little later,

Brian Davis took a job with Marconi. This left no one in R&D, and

the hierarchy took on a man as Technical Director. I cannot recall his

name, but he strutted into the laboratory with two assistants and

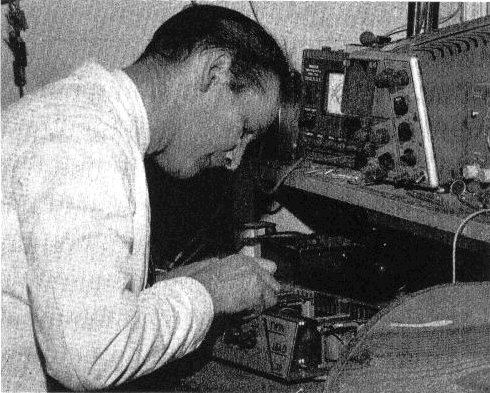

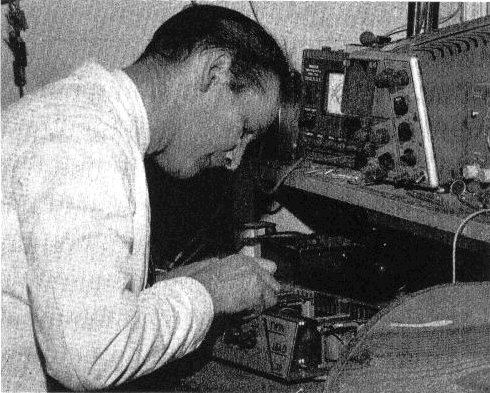

proceeded to do precisely nothing. At this time the Twin Lead 30

was causing problems due to it being a valve amplifier, but with a

germanium transistor pre-amp stage. These transistors became hot due to

the output valves being in their close proximity, and thus they failed.

Dick Twydell was under pressure from Sales to do something about it,

and he asked me what I thought could be done. I suggested that the

transistor needed to be replaced by a valve but there was very little

space to spare in the case. However, I said that I thought I could

figure it out and he told me to go ahead, and I believe that is what I

am doing in the photo published in 'Beat International'. With some

difficult manoeuvring I managed it and I took my prototype to Dick. He

told me to give it to the new Technical Director with the message that

he should prepare it for production. This I did, but the next day the

Technical Director came to me with the request that I make another

prototype. When I asked what

had happened to the original he told me that they had taken it to

pieces and were unable to put it together again! To say that I was

livid would be an understatement, and I blankly refused to have

anything to do with it. However, Dick asked me to collect the pieces

and organise the thing for production, and it was later re-launched as

the All-Purpose 30 (AP30).

.jpg)

October 1967 Selmer advertisement introducing

John Weir's new All-Purpose Twin 30, together with the new 100 watt Zodiac

and Thunderbird heads.

Because competition in the industry was fierce at that time, new

products were always needed, and the hierarchy decided that they wanted

an amplifier similar to the PA100 but having six channels with

reverberation on two of them, and this to be ready for showing at the

1967 Music Industries Fair which was held every summer in the Russell

Hotel in Bloomsbury. This assignment was given to the Technical

Director and his assistants.

As the 1967 Fair drew near, the Directors wanted to know where the new

amplifier was, and when it became obvious that the Technical Director

had failed to achieve anything at all, they were not best pleased to

state the least. All of the Selmer dealers had been told that the new

amplifier would be demonstrated at the Fair, and this was going to

leave the hierarchy with egg on their faces. After a great deal of

discussion they decided that a dummy would be made. An empty cabinet

with a front panel adorned with knobs and switches. This would be shown

at the Fair, with the comment that a few final touches were required

before it could be released. And so it was, but the hierarchy had had

enough. The Technical Director and his assistants were required to

resign forthwith. However, this left the company with a further problem

in that within a few months the next Music Industries Fair would be

upon them and they still did not have the 100 watt amplifier to show.

By this time I had rebuilt the AP30 and it had gone into production,

and largely on the strength of this, and also out of desperation, Dick

Twydell asked me if I thought I could tackle the design of the large

model. I had to weigh up the pro's and con's. To my advantage was the

fact that we already had a 100 watt amplifier with four channels, so

that I would be able to use some of the existing circuitry, but I would

have to add reverberation circuitry with two more channels. The

disadvantage that I saw was that I would have to use the same external

design and layout as the dummy model which had already been seen by the

Trade at the previous Fair. This I thought may or may not affect the

working of the finished unit, however, I saw this as my big chance and

felt confident that I would be able to overcome any problems, so I

accepted the challenge, and forthwith moved into the laboratory to

begin work.

After many problems, some of my own making, I managed to complete a

prototype six channel amplifier, and the Marketing Director came up to

the factory to hear and inspect it. Fortunately for me he gave it his

approval and it went into production as the PA100R in plenty of time for the 1968

Music Industries Fair. After this I continued working on various

development projects, including a small 5 watt amplifier (ED - the Mercury model)

to replace the 'Little Giant' which had been popular as a practice amp,

and the Directors showed their gratitude by promoting me to Technical

Manager.

.jpg)

February 1968 Selmer advertisement

introducing John Weir's new PA100 Reverberation amplifier.

The Selmer operation occupied three locations; the factory at Holborn,

the warehouse in Clerkenwell, and the showroom and head offices in

Charing Cross Road. The wind instrument repair shop was also at Charing

Cross Road, under the control of Charlie Wicks. Having assessed his

task, the Chairman concluded that the overheads on the three

establishments in central London were too great, and decided that it

would be financially advantageous if they could be brought together

into one unit, and preferably out of London. At that time the

Government was eager to encourage firms to move out of the city, and

the incentives they offered were very attractive. Cochrane looked at

several possibilities; even Dumfries in Scotland. However, our

associate company Selcol was situated in Braintree, Essex, where they

manufactured plastic mouldings, mainly of garden ornaments and toys.

(Ed - See Selcol's Plastic"Junior Beatle" Guitar

elsewhere on this website.) They were not doing very well and in late

1967 Cochrane sent Dick Twydell to Braintree to ascertain whether it

could be made viable. For various reasons it was not thought possible,

and a decision was made to close it down and move the whole Selmer

business into the Selcol premises, leaving only the Charing Cross Road

showroom and head offices in London.

During 1968 various people were interviewed and asked if they would

consider moving to Braintree, including myself. One of the Government

perks of moving was an allocation of houses and flats, and I was told

that I would get a flat if I accepted. As I seemed to be getting on

well I did not relish the thought of leaving Selmer, but on the other

hand, I liked living and working in London. I found it a difficult

decision to make, but in the end I agreed to go.

Twydell was given the task of arranging the evacuation of the Selcol

premises, and the transfer of the manufacturing plant from

Holborn. It was hoped that as least some of the employees at Braintree

would agree to remain and be trained to undertake the new work, but

unfortunately the management of the plastics business were less than

pleased with what was happening, and persuaded their staff to refuse

the offer.

On Friday 22th of November 1968 I was working at the Holborn

factory when I received a phone call from Braintree. It was Twydell. At

the last minute he had persuaded six of the female staff to stay, and

wanted me to be at the Braintree premises at 7.30am on Monday 25th, to

greet them and begin their training. He had taken the liberty of

booking me into a small hotel, 'The Old Court', which was fortunately

situated only about 100 yards along the road from the factory, and so

it was that I drove up and booked in at the hotel on the Sunday

afternoon.

Having to be at the factory at 7.30am the next morning, I wanted to be

sure of being on the premises early, and left the hotel just after 7am

which was too early for breakfast to be served, but luckily I found a

drinks machine in the factory and managed to get a cup of coffee. I was

soon confronted by six ladies who arrived for training, albeit somewhat

anxiously, as they were convinced that they would not be able to do the

work. However, my problems were only just beginning. I had been promise

that a couple of workbenches would be left in the production bay, with

sockets connected to the electricity supply, but because the management

were so sour about the transfer, they had made sure that all of the

benches were disconnected and moved into awkward positions.

I had brought an amplifier with me, so I placed it on an empty bench

and asked the ladies to examine and discuss it while I tried to sort

something out. Although the premises had been vacated, the toolroom

still existed in a small separate building, and the toolroom manager,

Keith Taylor, was going about his business. Unlike the others who had

left me in the lurch, Keith was very sympathetic and helped me to drag

two heavy benches into a suitable position, and wired a cable into an

adjacent fuse box to supply power to the benches. I soon had soldering

irons heated up and went to fetch the girls. Having looked closely at

the amplifier I had brought with me, they were now even more convinced

that they could not do the work, and my main problem was in persuading

them that if the London operators could do it, so could they. However,

I showed them how to solder some scrap pieces of wire together and left

them to practice for a while Then with some suitable compliments from

me with regard to their efforts, they settled down in a better frame of

mind.

It had been decided that a complete set of parts and equipment to build

25 PA100 amplifiers, would be sent down by lorry, and the consignment

duly arrived, and work was commenced. This kept us all busy, and as

there were no inspectors or test technicians I had to take on this job

myself. I should point out here that once the ladies had overcome their

initial doubts, they picked up the wiring and assembly skills

remarkably quickly, and I was pleasantly surprised at the quality of their

work. Dick Twydell visited us several times as also did the Chairman.

At the end of January 1969 the London operation closed down, except for

the Charing Cross Road showroom, and lorries began bringing all of the

stores and equipment to Braintree. I had started recruiting some staff

to augment the six girls, and things went fairly well at first, but the

lorry loads of materials were arriving so fast that it became

impossible to cope. I remember complaining to Twydell, but he had

promised the Chairman that the move would be completed by a certain

date and there was nothing to be done about it. I felt rather

despondent, especially when I viewed the huge mountains of materials

piled up over every inch of the floor area, but eventually staff were

sent up from London temporarily to assist in getting everything

straight, and so the problem gradually subsided.

Because most of the staff were new, it was necessary for me to spend

the majority of my time on the shop floor dealing with various

production problems, as well as keeping an eye on product development,

but I had engaged a reasonably good engineer, John Lawrence, and so for

the most part I left him to work on a new transistor amplifier, which

was to become the Taurus.

Nevertheless, due to the upheaval, we were unable to produce anything

new for the 1969 Music Industries Fair, much to the chagrin of the

sales department. However, I had been working on a 'Fuzz-Wah' foot

pedal before leaving Holborn, so this was completed and put into

production.

.jpg)

June 1986 Selmer advertisement for John

Weir's Fuzz-Wah pedal

A major change took place during that first year. I had been aware even

during the years in London, that Dick Twydell consistently made

promises to the sales department with regard to the availability of

goods being produced, which were not possible to be met by the actual

production

facility. Needless to state, this situation was causing considerable

upset, and the Sales Manager

kept complaining bitterly to the Chairman,who in his wisdom, decided

that Dick had to go. Although Dick and I had crossed swords on numerous

occasions, we had always understood each other and in fact it was

largely due to him that I had achieved my

position as Technical Manager, so I was rather sad that it had turned

out this way.

They engaged another Production Director before Twydell left. This guy

knew all the right things to say in order to impress the hierarchy, but

I soon realised that he was hardly suitable for our operation. He had

previously worked for a large television and radio company, and so

thought in terms of large scale production flow lines. This was

entirely unsuitable for our business where we needed flexibility to

produce a number of different types of amplifier and speaker in batches

of 25 or 50. He succeeded in alienating most of the production staff

and their output suffered. During this time the Chairman engaged a

manager to oversee the Service Department. He was also given the task

of devising a complete new look for our products. For this he hired a

Designer on a subcontract basis, who had no technical knowledge but was

in fact an artistic designer. After some study, the man put forward a

report complete with coloured drawings of what he felt was required.

His ideas would have probably been suitable for domestic Hi-Fi

equipment, but were totally unsuitable for our type of products which

had to stand up to the rough usage of people performing in pubs and

clubs, as well as looking attractive.

At the end of this first year I was told that a new range of

amplification equipment would be required for showing at the 1970 Trade

Fair. I had already anticipated this and had been giving the matter

some thought. Our dealers, having become disillusioned with transistor

amplifiers, had made it clear to our sales people that they were only

interested in purchasing valve equipment. I knew our existing range

well, and I had been made aware of what was currently in vogue, and on

the basis of 'If it ain't broke don't fix it', I decided that our

current products were quite good, but that by eliminating the weaknesses

and incorporating some new ideas put to me by young guitar players, I

should then have a suitable range, particularly if I gave it all a new

look, with thick, chunky cabinets which were then the fashion. Although

the Artistic Designer had not achieved what had been hoped for, I noted

that he had put forward an idea for the front panels which intrigued

me. This was that the panels of all similar models should be of the

same size, and all hole punchings should be made on the same matrix, so that

even those which only needed a few holes could be placed over any of the

others and the holes would line up. This would also make production cheaper

and easier. I incorporated this as far as possible into the new range, and

together with the other changes, produced a set of prototypes for the

approval of the management and sales staff. They were well received, and

launched as the SV range at the 1970 Fair.

.jpg)

September 1970 Selmer advertisement

introducing the new "SV" range.

At about this time there were rumblings of discontent among the organ

sales staff. It appeared that the American public preferred different

models to the British public. CMI refused to accept this and started to

discontinue those organs which did not sell well in the States. This

included the GAK which sold very well here. They began sending new

models over which failed to gain popularity in this country, and sales

were falling as a result.

Unfortunately, Selmer were never able to sell their amplification

equipment in the USA. I cannot be certain why this was, but I believe

it was due to an American company with the same name, objecting to the

import of goods with their logo. Obviously it would have made quite a

difference to the sales figures if this had not been the case. (ED -

this could have been due to rivalry between Henri Selmer's US company

and Selmer UK).

By 1971 the Sales team had realised that the trend was for more

powerful

amplifiers, and I was asked to develop a 200 watt outfit complete with

suitable speakers. A competition had been set up within the company to

find a name for it, and the winner put forward the name 'CHIEFTAIN', which was met with general approval.

I was requested to incorporate some features which had proved popular

in past models, such as push button tone changing, and this I did. In

order to take full advantage of the power, I had words with the guys at

Celestion and they came up with a 30 watt horn speaker. I incorporated

this into a cabinet with two 12 inch dual cone units for the high

frequencies, and also had a vented cabinet with four 12 inch units for

bass. Two of these set-ups were given to 'McGuiness Flint' who were a

popular group at that time, and they told me that they had to use them

with the horn units on the floor, as if they had them up higher they

blew their heads off!

.jpg)

July 1971 Selmer advertisement, showing

McGuiness Flint with their Chieftain amplifier outfit on the left.

About the summer of 1971, Dick Twydell's successor, after a succession

of disagreements with the Chairman, resigned and left the company.

Cochrane then called me to his office and told me that I was to take

over as Production Manager. I felt obliged to do so, but was not at all

happy about it, as I much preferred the technical development work

which I had been doing. However, the production figures had not been

good, due to the flow-line mentality instigated by the previous

Production Manager, which had upset the operators. My first move was to

revert to the batch production technique we had used previously, and I

put the operators on a bonus scheme so that they were able to earn more

for increased quantity and quality.

In early 1972 John Cochrane retired. His replacement was Michael

Nugent, a much younger man with a reputation as a Wizz-Kid. He

certainly proved to be a much better boss than his predecessor and

things improved quickly. However, his reputation spread to CMI and he

was soon invited to join their business in Chicago, so in barely a year

he left us for America, but the Board of our Holding Company refused to

release him from his contract until he had found a suitable person to

succeed him. He quickly found Malcolm Parkin, a man of similar age to

himself, but whether due to his haste to get to Chicago or not, his

choice soon proved to be a disaster.

Parkin and I did not get on too well, and the situation between us

quickly deteriorated as far as I was concerned. There were also strong

rumours that CMI had made an offer to buy Selmer in order to establish

a UK base. I therefore began thinking seriously about leaving, and

started investigating possible positions with other companies.

In September 1973 I left Selmer. Not long after, Chicago Musical

Instruments bought it, and it started to go downhill fast. Parkin

resigned and his place was taken by Dean Kerr who had been Marketing

Director. Dean was a fine trumpet player and had previously played with

the 'Clyde Valley Stompers' in his home town of Glasgow. I always got

along OK with Dean but he was not cut out to be Chairman. After a while

it became too much for him and he asked to step down. He was made

Managing Director and another Chairman was brought in. Due to the

attitude of the Americans regarding which model organs should sell well

in the UK, and the fact that they failed to develop any further

amplification products to meet the approval of the market, the business

gradually dwindled down. They eventually had to move out of the

Woolpack Lane premises, and into a much smaller unit on a factory

estate. I am not certain when they finally closed, but I believe it was

during the very early 80's. The Woolpack

Lane factory was used by another firm for a while, then stood empty

(and vandalised) for years. It was eventually bulldozed down in the mid

1990's and the site is now a private housing development.

So died a Company that had everything going for it during the 60's, but it all went wrong in the end. It's very sad.

JOHN WEIR

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)